Commanders!

If you’re into western Cold War “what if” military documentary TV shows or Youtube videos like we are, you are probably familiar with a sight of Soviet armored units advancing through Europe, each under the vigilant protection of a pair of Shilkas – the dreaded four-barrel self-propelled anti-aircraft guns. Their turrets sweep around, looking for NATO helicopters and aircraft to take down with rapid fire autocannon bursts, but not shying away from peppering buildings and other places where their opponents might be hiding using their combined rate of fire of 4.000 rounds per minute.

ZSU-23-4 Shilka

In these movies, the Soviet column is confronted by a platoon of American Abrams tanks, covered by the American AA system called.... no, that’s not how this usually goes. The Americans have no dedicated anti-aircraft vehicles that would act as Shilka counterparts – and for a good reason. Self-propelled anti-aircraft vehicles (or the lack thereof) have been a thorn in the side of American armored forces for a very long time and in today’s article, we’re going to take a look at a specific part of the American AA design evolution – the DIVAD program.

But, let us start at the beginning. Armored self-propelled anti-aircraft guns (SPAAG) started popping up during the second half of WW2, when the militaries that were involved in the fighting realized that assault aircraft posted serious threat to ground forces – after all, the typical howl of Junkers Ju-87 Stuka became one of the symbols of German Blitzkrieg. The Allies, naturally, developed their own ground attack planes, the most famous of them being the Soviet Sturmovik or the American Thunderbolt, which would wreak havoc on retreating German formations.

The standard tactics used by such aircraft would be either precise dive bombing or direct fire either by powerful cannons or by rockets. Even though their efficiency was routinely overestimated for a number of reasons (from destruction misidentification to simple pilot bragging), these attack runs were quite dangerous, especially to poorly protected truck-borne infantry, horses and other soft targets.

Of course, it’s not like the ground forces were entirely defenseless. Both static and towed AA guns existed even before the war since pretty much every army dreaded fighting enemy bombers. Massive static emplacements were constructed around major cities and other valuable targets, consisting of batteries of large guns, designed to hurl explosive shells to high altitude in order to ward off even large aerial assaults. These were constructed to fire en masse though, with shrapnel doing the dirty work – hitting anything smaller was mostly a matter of luck.

The thing was, the assault planes were small, so such strategic defenses weren’t really effective against them. Towed medium caliber AA guns (20-40mm) were better, but they had to be deployed first and preparing them to fire took some time. In other words, they weren’t perfect for protecting mobile formations on the move. That is why pretty much all sides started putting these guns on some suitable chassis – from tracks to modified tank hulls – and so the first mobile AA was born.

M16 MGMC

Mind you, these contraptions weren’t really all that effective at downing enemy aircraft. Hitting a small target by aiming a gun with just rudimentary optics wasn’t very common, but then again, that wasn’t their primary purpose. The primary purpose was to scare the marauders off and nothing scares off a pilot sitting in basically an unarmored coffin like a huge cloud of tracer rounds coming his way. Especially during the final years of the war with allied air supremacy being nearly total, the Germans found out that mounting several (former aircraft) machineguns on a halftrack and just firing in the general direction of an attack often simply worked and the attacker would fly away.

Plus, these guns could have easily been turned on ground targets – this is how the American contribution to this vehicle category, the M16 MGMC (armed with four .50 caliber heavy machineguns) earned its grizzly nickname – “meat chopper.”

And that’s how the war ended for the Americans – with the M16 in service as the main short range AA vehicle. Larger vehicles were being developed in the U.S.A., but – much like other advanced weapons – came too late to be shipped to Europe or the Pacific. After the end of the war, with the de-escalation, many projects were de-funded and abandoned, but the short range mobile AA research was recognized as critical and continued until the Korean War really kicked things up a notch.

M19 MGMC

One of the late war weapons that never got deployed, the M19, finally saw action on Korea. It consisted of two interesting elements – the wartime light tank chassis from a M24 Chaffee and the turret with two 40mm Bofors guns, giving it much longer reach than machinegun-armed the M16. The chassis was obsolete (and the M19 was phased out right after the war in the U.S. forces) but the 40mm guns turned out to be really, really effective against human wave-style Chinese attacks. It wasn’t pretty to watch, but definitely did the job.

But this was the true beginning of a jet era and even the early jets were too fast for simple optical acquisition, making such weapons as the M19 obsolete, which was why the Americans started to work during the Korean War on its replacement that would later be produced in thousands – we are, of course, talking about the M42 Duster (the name was unofficial but is so common today that we’ll continue to use it for this article).

The Duster was initially supposed to be paired with a radar system helping to aim its twin 40mm Bofors guns that turned out to be so effective before, but this feature was scrapped during the development process as too expensive and the Duster crews had to rely on its manual sights only. The vehicle was based on the M41 Walker Bulldog Light Tank and essentially had only very basic anti-bullet protection. The turret was also open-topped and, in summation, the Duster was deemed obsolete very quickly with its production run ending in 1960, the vehicle itself being phased out of service in 1963 and partially sold off to other, unsuspecting countries.

M42 Duster

Now, to some of you familiar with Vietnam War military photographs, this part might seem a little strange because the vehicle was clearly deployed there. But how could it have been deployed if it was long-phased out by then?

As many of you are already guessing, that was a part of a rather interesting situation. By the late 1950, the Atomic Age was in full swing with all sorts of interesting ideas taking root within the U.S. Army. One of these ideas, partially logical at the time but not exactly brilliant in hindsight, was the notion that anti-aircraft guns (both on the ground and on warplanes) were obsolete and that guided missiles such as the Hawk or the Sidewinder would take care of everything. After all, American scientists were working on helping astronauts to find their way in space – surely that would be more complex than helping a missile to find its way into a communist backside.

You can probably see where this is going. The Americans were too optimistic about the capabilities of early missile systems, which led to a number of bad decisions mostly on the Air Force side and eventually would spawn the abomination that was the F-104 Starfighter, one of the most lethal fighter jets in history (but only to its own pilots). On the ground side, as we mentioned above, the Duster production was stopped in 1960, but other promising SPAAG projects – such as the T249 Vigilante with its massive 37mm Gatling gun – were canceled as well.

T249 Vigilante

Their replacement was supposed to be the MIM-46 Mauler system that would fire beam-riding missiles at its target, but the program ran into such serious issues that it was canceled in 1963 with the focus shifting on less experimental solutions that were, however, more readily available. This turned out to be a combination of two platforms – one covering longer distances and one covering short ones.

The reason why this combination was chosen was rather simple. New Soviet ground attack planes were entering production and developing a joint platform for both tasks would take too long, so an interim solution was required. This essentially required the use of existing weapon systems. There was an older idea to push early Sidewinder missiles into a SAM (surface-to-air missile) role, but there was a major drawback to that concept.

While offering considerable range, these missiles were infrared-guided, targeting the aircraft engine heat. Apart from the abovementioned problems with early missiles in general (older Sidewinders got easily confused by other heat sources, even the sun), the system required a lot of time to lock on, making it therefore unusable at short distances. To compensate for that issue, a second platform with a gun would be introduced.

These two platforms became the MIM-72 Chaparral and the M163 VADS (also known under the name Vulcan after its main weapon). The Chaparral, using an M113 suspension, would fire missiles derived from the Sidewinder while the VADS was basically an M113 hull armed with a single 20mm Vulcan rotary cannon. While effective, the cannon had limited range only and had to rely on Chaparral’s support at long distances (and vice versa). But, more importantly, both systems would not be ready for the Vietnam War that was just picking up steam.

And the result of a decade of anti-aircraft research? Old mothballed Dusters were dusted off and sent to Vietnam. Luckily for the Americans, their air superiority was practically uncontested and these venerable machines were never really tasked with serious anti-aircraft protection duties. Instead, they were used as infantry support vehicles with their twin 40mm guns being just as deadly against Vietcong as they were against the Chinese two decades prior. Despite being generally obsolete and difficult to keep running, the Dusters performed admirably and broke many a Vietnamese ambush. They were finally phased out for good after the end of the conflict.

M163 VADS

Still, starting from the late 1960s and the early 1970s, the Vulcan/Chaparral combo became the main American mobile anti-aircraft means. On paper, it was a good, if rather expensive, combination (after all, you have two separate platforms to maintain), but another problem loomed on the horizon – helicopters. The Americans used attack helicopters such as the AH-1 Cobra to great effect during the Vietnam War and the later concept of AirLand battle emphasized the helicopter tank-killing ability (using guided missiles) as one of the key aspects of their use.

The thing was, the U.S. Army realized rather quickly that the Soviets would follow suit and would use their own helicopters (most notably their deadly Mi-24, also known under the nickname “flying tank”) in the same manner.

One popular helicopter tactic involved peeking from behind cover, firing a missile and then quickly getting in cover again. When using an advanced weapon system such as the 9K114 Shturm (that became available in the mid-1970s), a Soviet helicopter would make the Chaparral/Vulcan combination uniquely ineffective because:

- The launch of the Shturm missile was possible at 5km, which was well beyond the effective range of the Vulcan

- The time window between the launch and taking cover was way too short for a successful Chaparral missile lock and launch

In other words, under some circumstances (that the Soviets would surely exploit), American units in Europe were, when not under the protection of some static SAMs, left completely vulnerable to a Soviet helicopter onslaught.

MIM-72 Chaparral

As we stated before, the Chaparral/Vulcan combination was always considered as an interim measure and was planned to be replaced in the 1970s by a unified weapon system that would also have the following characteristics:

- The ability to target helicopters as well as low-flying planes at higher effective ranges than the Vulcan could

- Advanced targeting capabilities – the rudimentary radar of the Vulcan would just not cut it

- The ability the keep up with American armored formations, which essentially required a sturdy tracked chassis

- The ability to engage both ground and air targets

- Closed turret to address the vulnerabilities of the M42 Duster in ground attack role

And so, in the mid-1970s, a program was launched to provide the U.S. Army with just that. The program was called Division Air Defense (DIVAD).

The very first question that came up when evaluating the previous performance of the Vulcan was that of its caliber. Twenty millimeters were just not going to cut it – despite its declared maximum range of roughly five kilometers, the gun was only effective at two at best. The shells were just too light and would fly all over the place afterwards.

On paper, increasing the caliber of an anti-aircraft weapon would produce much longer effective range, which was why 30mm to 40mm calibers were looked at. Burst capability was also a must due to the extremely limited time window the target is exposed to your gun, so you can’t go all that crazy with gun calibers, but something bigger than the Vulcan was deemed a must.

As a result, the authorities responsible for the program specified several weapons that would do the job and would be considered. These included:

- 30mm Mauser autocannon (still in development at the time)

- 35mm Oerlikon twin guns (still in development at the time, used for the German Gepard)

- 30mm GAU-8A Avenger (yes, the same gun the A-10 Thunderbolt II uses)

- 35mm Gatling gun of the same type Sperry used for its T249 Vigilante

- 40mm Bofors twin L/70 guns (being the most conventional candidate)

A request was made in April 1977 for military companies to submit their proposals for the program. The following companies were contacted:

- Ford

- General Dynamics

- General Electric

- Raytheon

- Sperry

The specified goal of the proposals was to use as many existing parts as possible in order to make it cheap and readily available. Two best proposals would then get a prototype contract with a deadline of 29 months and would be provided with a modified M48A5 tank chassis to mount their turrets.

CA-1 Cheetah - the Raytheon proposal image is not available, but swap the hull with an M48 and you have the result

Raytheon proposed to mount the chassis with what was basically a modified German Flakpanzer Gepard turret armed with two 35mm Oerlikon guns. This was an interesting solution because the system already existed and was in Dutch service under the name CA-1 Cheetah – and Raytheon was licensed to produce it for U.S. purposes. On the other hand, using foreign equipment was never terribly appealing to the Americans.

General Electric produced what was perhaps the coolest DIVAD proposal. They proposed a turret armed with the 30mm Avenger rotary cannon and guided by advanced radar. The Avenger, as you know, is a beast of a gun, doubling the effective range of the Vulcan and dwarfing it in sheer size and firepower.

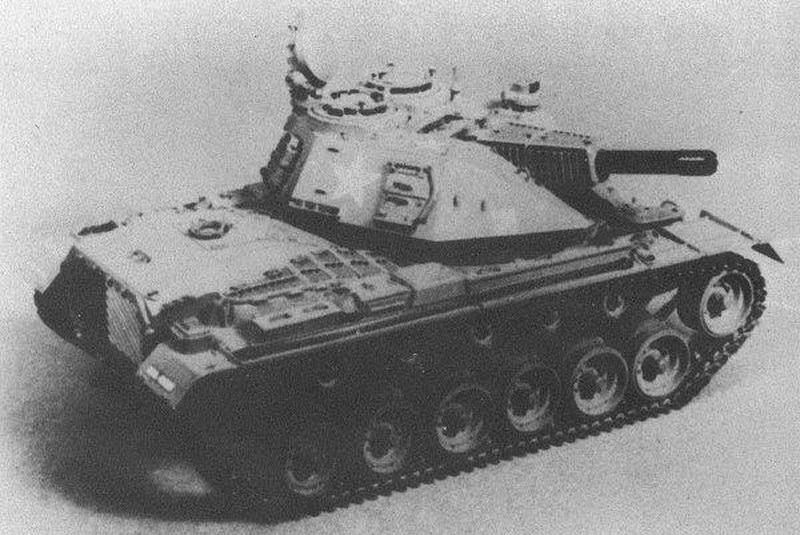

Sperry, the original developer of the ill-fated T249 Vigilante, based its entry on the previous design and armed the DIVAD proposal with a massive Gatling gun, scaled down to 35mm to fire standard NATO ammunition. As massive as the Avenger, the Sperry gun required a large turret made of aluminum to save some weight. This turret would be then fitted with advanced radars and electronics, including an IFF system. As an interesting feature, the gun would operate in two modes – an anti-aircraft one with 3000 rounds per minute rate of fire and an anti-ground one with 180 rounds per minute, which was deemed sufficient to destroy soft targets.

General Dynamics used the same weapon system as Raytheon (twin 35mm KDA guns), but that’s where the similarity ended. The turret was designed as brand new and its Fire Control System was derived from that of the Phalanx, another (static) anti-aircraft system that had already been in production at that point.

And, last but (unfortunately) not least, Ford came up with a proposal they called the Gunfighter with twin 40mm Bofors guns in an enclosed turret. These guns didn’t fire as fast as the other ones on the list (600 rounds per minute), their shells were, however, much bigger with fragments covering wider area. Ford effectively traded volume of fire for lethality. The radar was derived from the system used on F-16 Fighting Falcon fighter jets.

All these proposals were evaluated and, in 1978, Ford and General Dynamics were declared as winners with each company given the promised contract for a prototype. The General Dynamics prototype would be known as the XM246 while the Ford prototype received the XM247 designation.

This would start one of the most infamous chapters in the U.S. Army history – the story of XM247 Sergeant York. But that is a story for another time as we will cover the conclusion of the program in a different article.

And since this is a website about Armored Warfare, we are happy to inform you of the following:

One or more of the DIVAD program vehicles will appear in the game in Update 0.30.

Which one would you like to see the most? Let us know on Discord.

Stay also tuned for more info we’ll see you on the battlefield!