The OT-64 armored transport was and still remains a relatively successful Warsaw Pact-era wheeled APC. It was produced until the 1970s, and with over 4000 made many are still in service or are held in reserve by former users such as the Czech Republic, the Slovak Republic and Poland. While its concept is relatively outdated now with more and more emphasis being put on crew safety, it’s an affordable vehicle and the ease of its maintenance makes for an attractive choice for militaries without extensive resources.

SKOT-2AP

Its name: SKOT is actually an abbreviation for Střední Kolový Obrněný Transportér (Czech) or Średni Kołowy Opancerzony Transporter (Polish), with both versions having the same meaning: Medium Wheeled Armored Transport. But how – and, more importantly, why – was it actually developed?

The Beginnings of the Czechoslovak APC Development

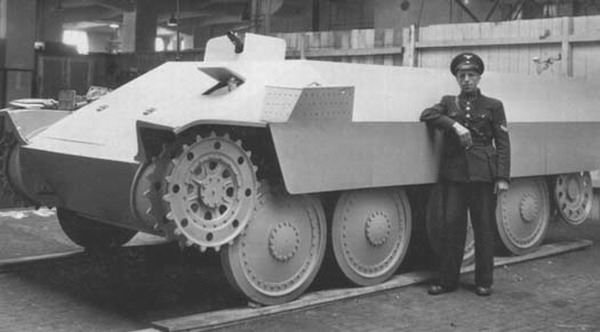

The original idea behind the SKOT was to develop something to replace the “standard” Czechoslovak APC of the late 1940s and early to mid-1950s, the captured German HKL6p halftrack (better known under its military designation Sd.Kfz.251). Using captured German vehicles was a necessity for the newly re-established Czechoslovak army in 1945, but it was always a stopgap measure until the production of either indigenous or licensed vehicles started in earnest and by 1955-1956, the halftracks were in a seriously worn condition and a replacement was required. Unfortunately, the wartime development of a very promising full-tracked APC on a modified LT vz.38 chassis (called the Kätzchen) was all but forgotten and the HKL6p replacement turned out to be just as bad as its predecessor (the infamous OT-810, nicknamed “Hitler’s Revenge” for its “qualities”).

Kätzchen APC

It is a common misconception that the development of a future wheeled transport vehicle began with the aim of replacing the OT-810, but this is not true. Instead the early development ran in parallel with the OT-810 and the replacement only happened later.

By 1954, a program was underway in Czechoslovakia to develop two variants of the future APC – one with tracks and one with wheels. The requirements included the ability to transport 12-15 troopers and, interestingly enough, mortar carriers and anti-tank variants (carrying an 82mm recoilless rifle) were envisaged right from the start as well. The most important demand however was to unify as many parts as possible with the Praga V3S truck (which turned out to interfere with the production of the aforementioned truck). The development was planned to begin in 1955 and the production start was estimated (more or less realistically) for 1960.

OT-810 with disembarking soldiers - source: valka.cz

These demands turned out to be too much for the still recovering Czechoslovak industry combined with the post-war development chaos, which was made even worse by the communist coup in 1948. There were three parties involved in the decision-making:

- The army, which followed the modern trends and wanted to equip its forces with armored carriers that drastically increased unit mobility and protection

- The politicians, who had no desire to invest in the development of indigenous designs and always considered the APC development as something temporary until a sufficient number of foreign (Soviet) vehicles could be purchased or license-built

- The industry representatives, who were already under strain to produce enough items for regular use (especially automobile engines, which were in short supply and turned out to be the bottleneck for APC production due to part unification requirements)

Furthermore, post-war Czechoslovakia developed and produced a large number of prototype designs in small production runs (for example, no fewer than 3 different halftracks), something that really annoyed industry representatives. Generally speaking, the industry tried to avoid the production altogether, politicians wanted to buy or license-produce Soviet vehicles and the military just wanted something better than the worn-out German halftracks as soon as possible. Another element that brought chaos to the process was the founding of the Warsaw Pact in 1955, one element of which was the agreement on equipment unification. Nobody knew, however, what equipment was supposed to be unified and to what degree, leading to further development (and production) delays. The APC issue was only clarified in 1956 when an agreement was reached between the Soviets and the Czechoslovaks – the matter was to remain purely in Czechoslovak hands.

Trial and Error

These talks did not (much to the industry’s dismay) mean that the development of various projects was halted for the time being. In 1956, two prototypes of the V3SO (armored version of the V3S truck) were trialed against another APC prototype, the HAKO halftrack, and in 1957 more trials took place (this time, they were compared to the Soviet BTR-152). The V3SO concept was never considered to be a serious future equipment proposal, it was another stopgap measure and by all accounts both prototypes fared pretty terribly. Even so, they managed to defeat the BTR-152 in trials (if only barely), but were completely inferior to the HAKO halftrack concept (the HAKO would later become the OT-810). The disastrous results of these trials ended in significant delays in further wheeled APC development.

The second V3SO prototype - source: M.Dubánek

It was clear that just up-armoring a truck would never produce acceptable results and a different direction was needed as early as in 1956. This time, military representatives (22nd Military Academy Division) with the help of (former) Praga and Tatra Kopřivnice proposed a 4-axle APC. For its time it was quite a modern 12 ton design, theoretically capable of reaching 80 km/h with the newly developed Tatra T-928K engine. Most importantly, it was a brand new construction and not a truck conversion. It still had some glaring flaws, but it was the first step towards what would later be known as the OT-64.

Matters were complicated by the 1957 requirement to make the vehicle amphibious. Amphibious vehicles were something the Soviets specialized in – they were based on the theory that Europe is divided by many rivers and other bodies of water and that for any successful operation in the region, vehicles would need to be able to cross them. In the end, this requirement was never really proven correct (at least not in Europe) and it only led to sacrifices in vehicle performance (for example the BMP series), but on paper it was impressive. On September 19, 1956, the army issued new demands for its wheeled and tracked amphibious transports (the tracked variant would become the OT-62 TOPAS). The task to build the wheeled vehicle was given the designation of SKOT in November 1956. The task didn’t have very high priority due to the production of the OT-810. Even if successful, first production vehicles were not expected to arrive before 1962. The exact demands for the SKOT vehicle were issued in early 1957 and were quite different from what the vehicle would later become. The earliest SKOT proposal was to have only 3 axles and was supposed to be able to carry 22 people or 3 tons of materiel. Its maximum operating range was to be 500km and its maximum speed 80 km/h. Its frontal 15mm armor was to withstand 12.7mm armor-piercing ammunition impacts while the sides and rear were to be resistant against 7.92mm AP ammunition. The vehicle was to be amphibious with a 6 km/h maximum swimming speed. In 1957, these requirements were approved by the Soviet Warsaw Pact command (with the only suggestion being to increase the swimming speed to 8-10 km/h), but another complication appeared as the industry was once again unable to deal with the number of projects developed for 1960-1965 military production. A decision was taken to reduce the amount of projects and develop the remaining ones more quickly.

SKOT 2A in the Polish Army Museum - photo by Hubert Śmietanka

As a part of this initiative, based on consultations with the military, the requirement to make the vehicle amphibious was re-evaluated. Apart from it being almost useless – tests of various prototypes have shown that even specialized tracked amphibious vehicles have problems climbing onto shores not previously leveled by engineers – the development of the non-amphibious variant would be ready one year earlier (2-3 years) and would cost half as much. In the meantime, Poland – interested in purchasing an APC as well – started shopping around. At this point, the Polish did not yet have any influence on SKOT development, but they certainly knew about it (Polish cooperation talks started in earnest in 1961 and in 1962 Polish experts participated in the trials of one of the SKOT prototypes). The project suffered from other problems as well (no state-owned company was exactly enthusiastic to develop it further, citing full capacities) and the development dragged on with many matters undecided.

SKOT 2A during military exercises in Poland

In the end, it was the politicians who decided the whole matter. In 1957, citing slow progress and very high costs for military development between 1951 and 1956, a great number of projects were pruned from long-term plans after a Politburo intervention and those that remained were given priority. The SKOT pre-project was approved on March 7, 1958 and the preliminary design itself was approved on June 20, 1958. At this point, it was still unclear whether the vehicle would be amphibious or not, but that was about to change – despite protests from the Czechoslovak military and after some negotiations within the Warsaw Pact, the Soviets recommended the vehicle be made amphibious after all – and Soviet “recommendations” were not taken lightly. It was under these circumstances that the final design of the OT-64 was approved.

Sources:

- M.Burian, J.Dítě, M.Dubánek – OT-64 SKOT

- M.Dubánek – Trnitá cesta k zadání úkolu SKOT

- M.Dubánek – Od Bodáku po Tryskáče: Nedokončené československé zbrojní projekty 1945-1955

- Author's own archive collection